ECOCIDE

noun

destruction of the natural environment, especially when deliberate.

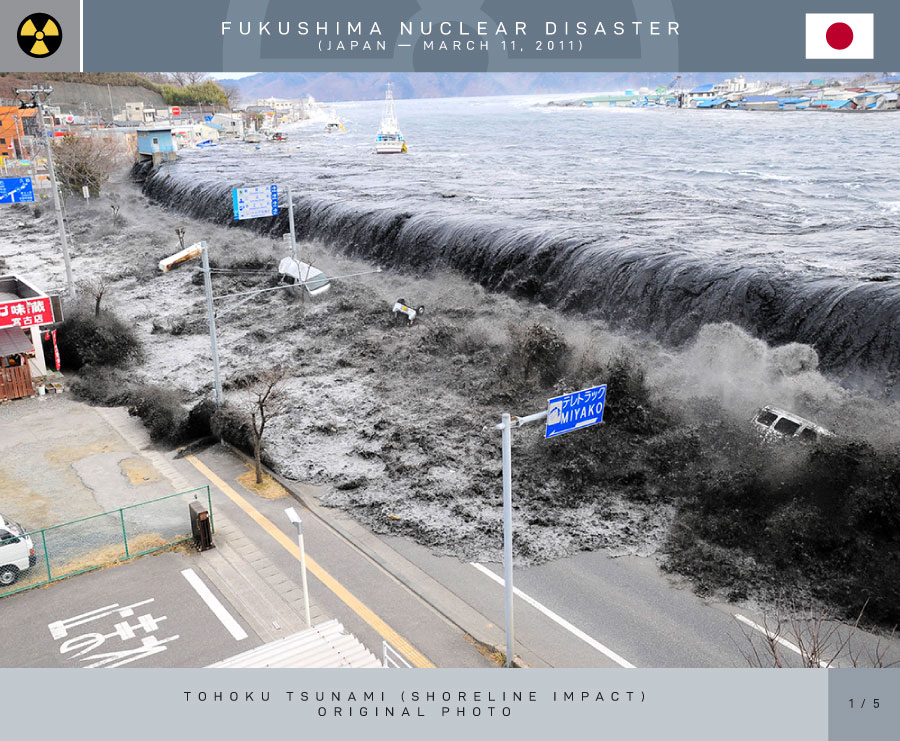

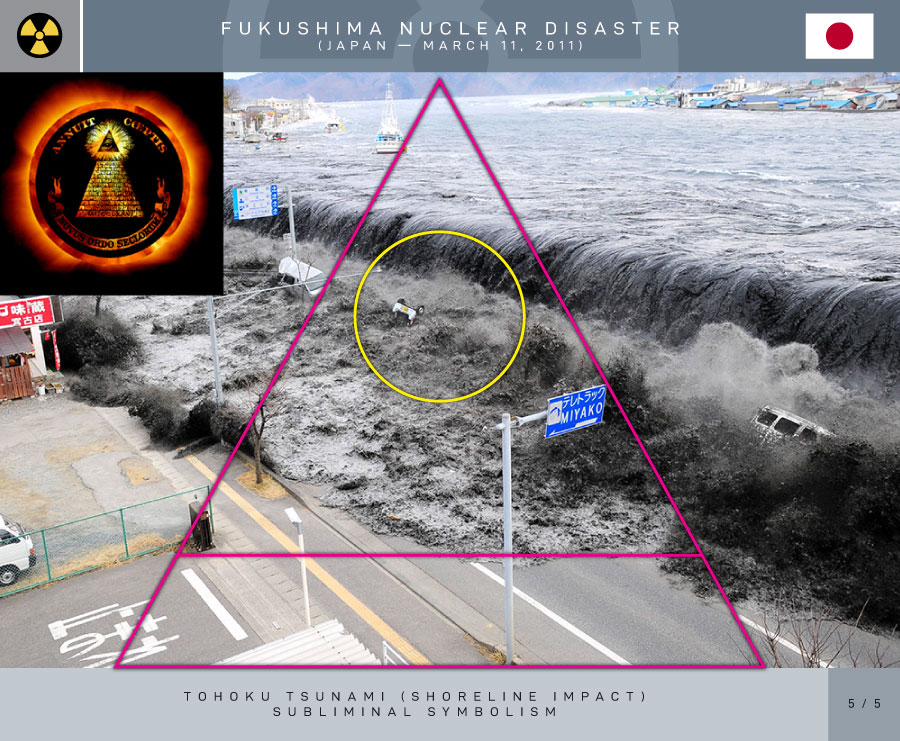

Tōhoku Tsunami

An upthrust of 6 to 8 metres (20 to 26 ft) along a 180 kilometres (110 mi) wide seabed at 60 kilometres (37 mi) offshore from the east coast of Tōhoku resulted in a major tsunami that brought destruction along the Pacific coastline of Japan’s northern islands. Thousands of lives were lost and entire towns were devastated. The tsunami propagated throughout the Pacific Ocean region reaching the entire Pacific coast of North and South America from Alaska to Chile. Warnings were issued and evacuations were carried out in many countries bordering the Pacific. Although the tsunami affected many of these places, the heights of the waves were minor. Chile’s Pacific coast, one of the farthest from Japan at about 17,000 kilometres (11,000 mi) away, was struck by waves 2 metres (6.6 ft) high, compared with an estimated wave height of 38.9 metres (128 ft) at Omoe peninsula, Miyako city, Japan.

Japan

The tsunami warning issued by the Japan Meteorological Agency was the most serious on its warning scale; it was rated as a “major tsunami”, being at least 3 metres (9.8 ft) high. The actual height prediction varied, the greatest being for Miyagi at 6 metres (20 ft) high. The tsunami inundated a total area of approximately 561 square kilometres (217 sq mi) in Japan.

The earthquake took place at 14:46 JST (UTC 05:46) around 67 kilometres (42 mi) from the nearest point on Japan’s coastline, and initial estimates indicated the tsunami would have taken 10 to 30 minutes to reach the areas first affected, and then areas farther north and south based on the geography of the coastline. At 15:55 JST, a tsunami was observed flooding Sendai Airport, which is located near the coast of Miyagi Prefecture, with waves sweeping away cars and planes and flooding various buildings as they traveled inland. The impact of the tsunami in and around Sendai Airport was filmed by an NHK News helicopter, showing a number of vehicles on local roads trying to escape the approaching wave and being engulfed by it. A 4-metre-high (13 ft) tsunami hit Iwate Prefecture. Wakabayashi Ward in Sendai was also particularly hard hit. At least 101 designated tsunami evacuation sites were hit by the wave.

Tōhoku Tsunami

(Miyako Harbor, Iwate Prefecture)

Like the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, the damage by surging water, though much more localized, was far more deadly and destructive than the actual quake. Entire towns were destroyed in tsunami-hit areas in Japan, including 9,500 missing in Minamisanriku; one thousand bodies had been recovered in the town by 14 March 2011.

Among the factors in the high death toll was the unexpectedly large water surge. The sea walls in several cities had been built to protect against tsunamis of much lower heights. Also, many people caught in the tsunami thought they were on high enough ground to be safe. According to a special committee on disaster prevention designated by the Japanese government, the tsunami protection policy had been intended to deal with only tsunamis that had been scientifically proved to occur repeatedly. The committee advised that future policy should be to protect against the highest possible tsunami. Because tsunami walls had been overtopped, the committee also suggested, besides building taller tsunami walls, also teaching citizens how to evacuate if a large-scale tsunami should strike.

Large parts of Kuji and the southern section of Ōfunato including the port area were almost entirely destroyed. Also largely destroyed was Rikuzentakata, where the tsunami was three stories high. Other cities destroyed or heavily damaged by the tsunami include Kamaishi, Miyako, Ōtsuchi, and Yamada (in Iwate Prefecture), Namie, Sōma, and Minamisōma (in Fukushima Prefecture) and Shichigahama, Higashimatsushima, Onagawa, Natori, Ishinomaki, and Kesennuma (in Miyagi Prefecture). The most severe effects of the tsunami were felt along a 670-kilometre-long (420 mi) stretch of coastline from Erimo, Hokkaido, in the north to Ōarai, Ibaraki, in the south, with most of the destruction in that area occurring in the hour following the earthquake. Near Ōarai, people captured images of a huge whirlpool that had been generated by the tsunami. The tsunami washed away the sole bridge to Miyatojima, Miyagi, isolating the island’s 900 residents. A 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high tsunami hit Chiba Prefecture about 2½ hours after the quake, causing heavy damage to cities such as Asahi.

On 13 March 2011, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) published details of tsunami observations recorded around the coastline of Japan following the earthquake. These observations included tsunami maximum readings of over 3 metres (9.8 ft) at the following locations and times on 11 March 2011, following the earthquake at 14:46 JST:

- 15:12 JST – off Kamaishi – 6.8 metres (22 ft)

- 15:15 JST – Ōfunato – 3.2 metres (10 ft) or higher

- 15:20 JST – Ishinomaki-shi Ayukawa – 3.3 metres (11 ft) or higher

- 15:21 JST – Miyako – 4 metres (13 ft) or higher

- 15:21 JST – Kamaishi – 4.1 metres (13 ft) or higher

- 15:44 JST – Erimo-cho Shoya – 3.5 metres (11 ft)

- 15:50 JST – Sōma – 7.3 metres (24 ft) or higher

- 16:52 JST – Ōarai – 4.2 metres (14 ft)

Many areas were also affected by waves of 1 to 3 metres (3 ft 3 in to 9 ft 10 in) in height, and the JMA bulletin also included the caveat that “At some parts of the coasts, tsunamis may be higher than those observed at the observation sites.” The timing of the earliest recorded tsunami maximum readings ranged from 15:12 to 15:21, between 26 and 35 minutes after the earthquake had struck. The bulletin also included initial tsunami observation details, as well as more detailed maps for the coastlines affected by the tsunami waves.

JMA also reported offshore tsunami height recorded by telemetry from moored GPS wave-height meter buoys as follows:

- offshore of central Iwate (Miyako) – 6.3 metres (21 ft)

- offshore of northern Iwate (Kuji) – 6 metres (20 ft)

- offshore of northern Miyagi (Kesennuma) – 6 metres (20 ft)

On 25 March 2011, Port and Airport Research Institute (PARI) reported tsunami height by visiting the port sites as follows:

- Port of Hachinohe – 5–6 metres (16–20 ft)

- Port of Hachinohe area – 8–9 metres (26–30 ft)

- Port of Kuji – 8–9 metres (26–30 ft)

- Port of Kamaishi – 7–9 metres (23–30 ft)

- Port of Ōfunato – 9.5 metres (31 ft)

- Run up height, port of Ōfunato area – 24 metres (79 ft)

- Fishery port of Onagawa – 15 metres (49 ft)

- Port of Ishinomaki – 5 metres (16 ft)

- Shiogama section of Shiogama-Sendai port – 4 metres (13 ft)

- Sendai section of Shiogama-Sendai port – 8 metres (26 ft)

- Sendai Airport area – 12 metres (39 ft)

The tsunami at Ryōri Bay, Ōfunato reached a height of 40.1 metres (132 ft) (run-up elevation). Fishing equipment was scattered on the high cliff above the bay. At Tarō, Iwate, the tsunami reached a height of 37.9 metres (124 ft) up the slope of a mountain some 200 metres (660 ft) away from the coastline. Also, at the slope of a nearby mountain from 400 metres (1,300 ft) away at Aneyoshi fishery port of Omoe peninsula in Miyako, Iwate, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology found estimated tsunami run up height of 38.9 metres (128 ft). This height is deemed the record in Japan historically, as of reporting date, that exceeds 38.2 metres (125 ft) from the 1896 Meiji-Sanriku earthquake. It was also estimated that the tsunami reached heights of up to 40.5 metres (133 ft) in Miyako in Tōhoku’s Iwate Prefecture. The inundated areas closely matched those of the 869 Sanriku tsunami.

A Japanese government study found that 58% of people in coastal areas in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures heeded tsunami warnings immediately after the quake and headed for higher ground. Of those who attempted to evacuate after hearing the warning, only five percent were caught in the tsunami. Of those who didn’t heed the warning, 49% were hit by the water.

Delayed evacuations in response to the warnings had a number of causes. The tsunami height that had been initially predicted by the tsunami warning system was lower than the actual tsunami height; this error contributed to the delayed escape of some residents. The discrepancy arose as follows: in order to produce a quick prediction of a tsunami’s height and thus to provide a timely warning, the initial earthquake and tsunami warning that was issued for the event was based on a calculation that requires only about three minutes. This calculation is, in turn, based on the maximum amplitude of the seismic wave. The amplitude of the seismic wave is measured using the JMA magnitude scale, which is similar to Richter magnitude scale. However, these scales “saturate” for earthquakes that are above a certain magnitude (magnitude 8 on the JMA scale); that is, in the case of very large earthquakes, the scales’ values change little despite large differences in the earthquakes’ energy. This resulted in an underestimation of the tsunami’s height in initial reports. Problems in issuing updates also contributed to delays in evacuations. The warning system was supposed to be updated about 15 minutes after the earthquake occurred, by which time the calculation for the moment magnitude scale would normally be completed. However, the strong quake had exceeded the measurement limit of all of the teleseismometers within Japan, and thus it was impossible to calculate the moment magnitude based on data from those seismometers. Another cause of delayed evacuations was the release of the second update on the tsunami warning long after the earthquake (28 minutes, according to observations); by that time, power failures and similar circumstances reportedly prevented the update from reaching some residents. Also, observed data from tidal meters that were located off the coast were not fully reflected in the second warning. Furthermore, shortly after the earthquake, some wave meters reported a fluctuation of “20 centimetres (7.9 in)”, and this value was broadcast throughout the mass media and the warning system, which caused some residents to underestimate the danger of their situation and even delayed or suspended their evacuation.

In response to the aforementioned shortcomings in the tsunami warning system, JMA began an investigation in 2011 and updated their system in 2013. In the updated system, for a powerful earthquake that is capable of causing the JMA magnitude scale to saturate, no quantitative prediction will be released in the initial warning; instead, there will be words that describe the situation’s emergency. There are plans to install new teleseismometers with the ability to measure larger earthquakes, which would allow the calculation of a quake’s moment magnitude scale in a timely manner. JMA also implemented a simpler empirical method to integrate, into a tsunami warning, data from GPS tidal meters as well as from undersea water pressure meters, and there are plans to install more of these meters and to develop further technology to utilize data observed by them. To prevent under-reporting of tsunami heights, early quantitative observation data that are smaller than the expected amplitude will be overridden and the public will instead be told that the situation is under observation. About 90 seconds after an earthquake, an additional report on the possibility of a tsunami will also be included in observation reports, in order to warn people before the JMA magnitude can be calculated.

Source: Wikipedia

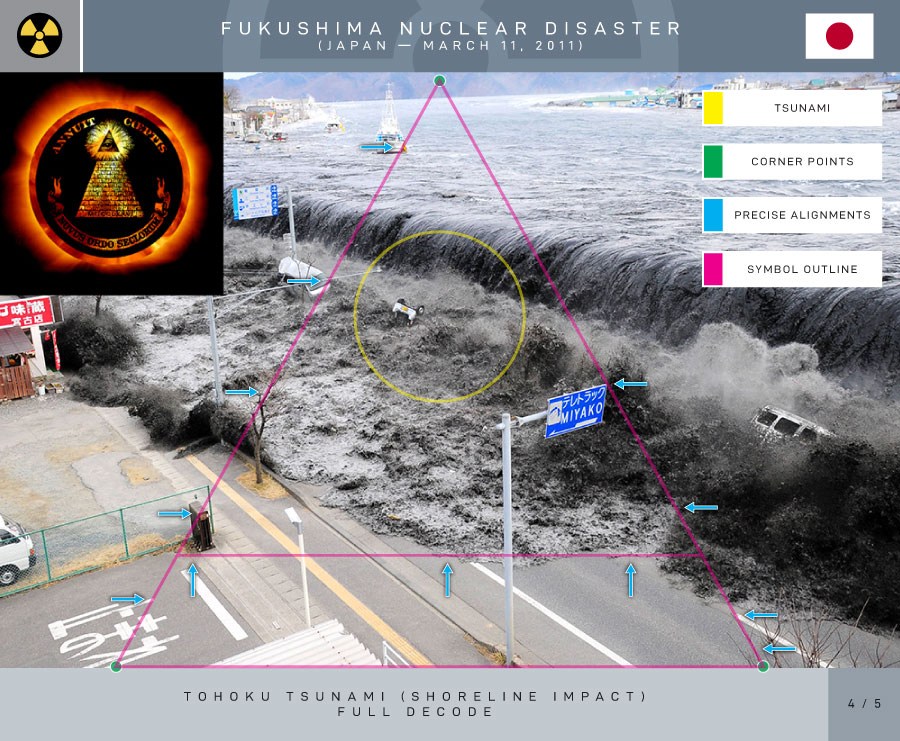

False Flag

A false flag is a covert operation designed to deceive; the deception creates the appearance of a particular party, group, or nation being responsible for some activity, disguising the actual source of responsibility.

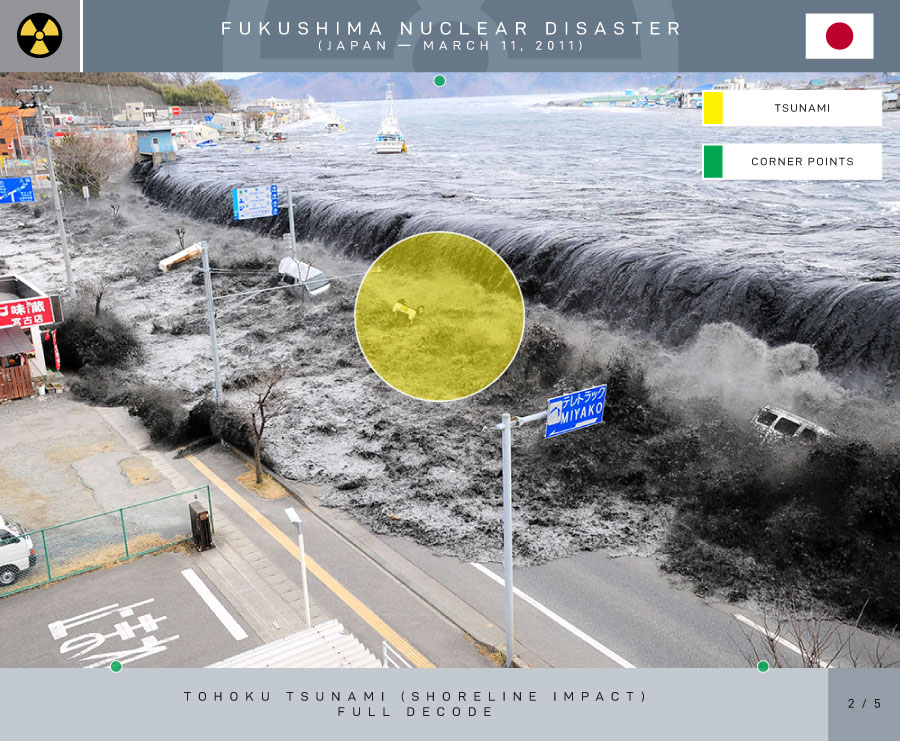

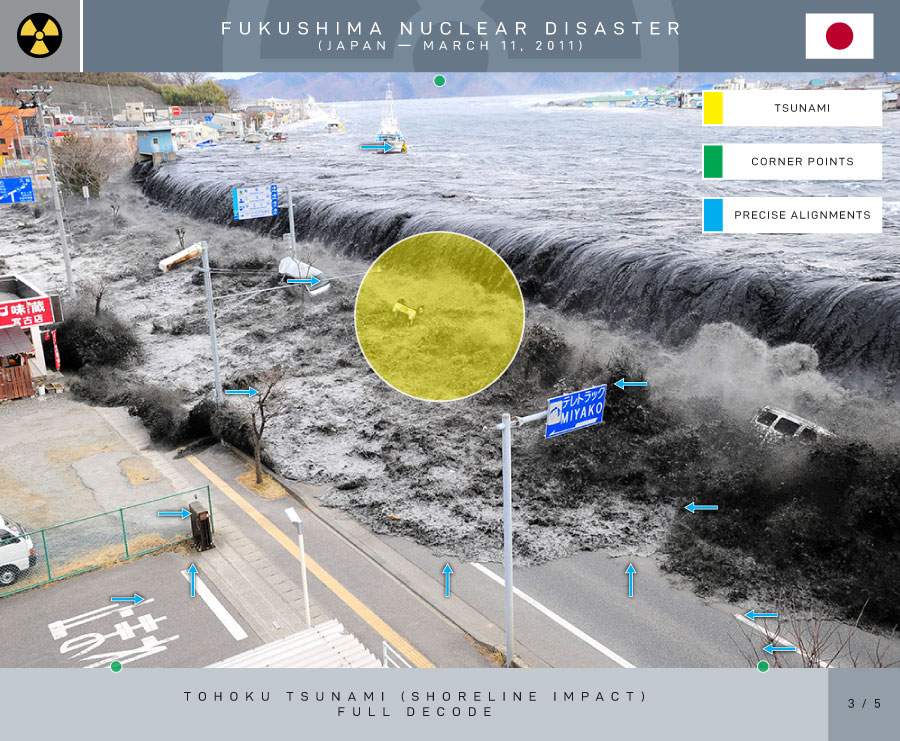

1.1 – Tōhoku Tsunami Shoreline Impact

(Miyako Harbor, Iwate Prefecture)

Subliminal Symbolism

The Invisible Symbol

Historical Truth

Continue Reading (Part 1.2)

END RADIOACTIVE DUMPING

SAVE THE OCEANS

HOLD THEM ALL ACCOUNTABLE

You must be logged in to post a comment.